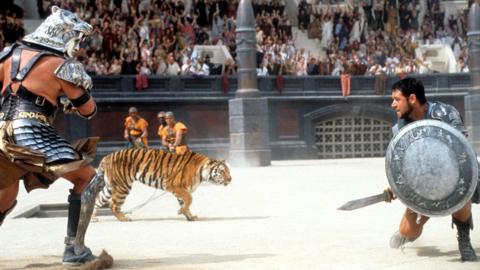

Bite marks found on the skeleton of a Roman gladiator are the first archaeological evidence of combat between a human and a lion, experts say.

The remains were discovered during a 2004 dig at Driffield Terrace, in York, a site now thought to be the world's only well-preserved Roman gladiator cemetery.

Forensic examination of the skeleton of one young man has revealed that holes and bite marks on his pelvis were most likely caused by a lion.

Prof Tim Thompson, the forensic expert who led the study, said this was the first "physical evidence" of gladiators fighting big cats.