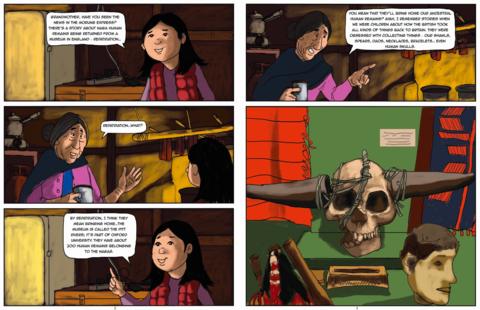

Last month, Ellen Konyak was shocked to discover that a 19th-Century skull from the north-eastern Indian state of Nagaland was up for auction in the UK.

The horned skull of a Naga tribesman was among thousands of items that European colonial administrators had collected from the state.

Konyak, a member of the Naga Forum for Reconciliation (NFR) which is making efforts to bring these human remains back home, says the news of the auction disturbed her.

“To see that people are still auctioning our ancestral human remains in the 21st Century was shocking,” she said. “It was very insensitive and deeply hurtful.”

The Swan at Tetsworth, the UK-based antique centre that put the skull on auction, advertised it as part of their “Curious Collector Sale”, valued between £3,500 ($4,490) and £4,000 ($5,132). Alongside the skull - which is from a Belgian collection – the sale listed shrunken heads from the Jivaro people of South America and skulls from the Ekoi people of West Africa.

Naga scholars and experts protested against the sale. The chief minister of Nagaland, Konyak’s home state, wrote a letter to the Indian foreign ministry describing the act as “dehumanising” and “continued colonial violence upon our people”.

The auction house withdrew the sale following the outcry, but for the Naga people the episode revived memories of their violent past, prompting them to renew calls for the repatriation of their ancestral remains stored or displayed far from their homeland.

Scholars suggest that some of these human remains were bartered items or gifts, but others may have been taken away without the consent of their owners.