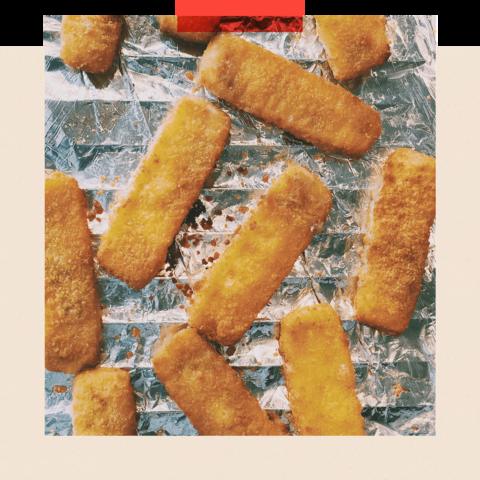

They are the bête noire of many nutritionists - mass-produced yet moreish foods like chicken nuggets, packaged snacks, fizzy drinks, ice cream or even sliced brown bread.

So-called ultra-processed foods (UPF) account for 56% of calories consumed across the UK, and that figure is higher for children and people who live in poorer areas.

UPFs are defined by how many industrial processes they have been through and the number of ingredients - often unpronounceable - on their packaging. Most are high in fat, sugar or salt; many you’d call fast food.

What unites them is their synthetic look and taste, which has made them a target for some clean-living advocates.

There is a growing body of evidence that these foods aren’t good for us. But experts can’t agree how exactly they affect us or why, and it’s not clear that science is going to give us an answer any time soon.

While recent research shows many pervasive health problems, including cancers, heart disease, obesity and depression are linked to UPFs, there’s no proof, as yet, that they are caused by them.

For example, a recent meeting of the American Society for Nutrition in Chicago was presented with an observational study of more than 500,000 people in the US. It found that those who ate the most UPFs had a roughly 10% greater chance of dying early, even accounting for their body-mass index and overall quality of diet.

In recent years, lots of other observational studies have shown a similar link - but that’s not the same as proving that how food is processed causes health problems, or pinning down which aspect of those processes might be to blame.

So how could we get to the truth about ultra-processed food?

The kind of study needed to prove definitively that UPFs cause health problems would be extremely complex, suggests Dr Nerys Astbury, a senior researcher in diet and obesity at Oxford University.

It would need to compare a large number of people on two diets – one high in UPFs and one low in UPFs, but matched exactly for calorie and macronutrient content. This would be fiendishly difficult to actually do.

Participants would need to be kept under lock and key so their food intake could be tightly managed. The study would also need to enrol people with similar diets as a starting point. It would be extremely challenging logistically.

And to counter the possibility that people who eat fewer UPFs might just have healthier lifestyles such as through taking more exercise or getting more sleep, the participants of the groups would need to have very similar habits.

“It would be expensive research, but you could see changes from the diets relatively quickly,” Dr Astbury says.

Funding for this type of research could also be hard to come by. There might be accusations of conflicts of interest, since researchers motivated to run these kind of trials may have an idea of what they want the conclusions to be before they started.

These trials couldn’t last for very long, anyway - too many participants would most likely drop out. It would be impractical to tell hundreds of people to stick to a strict diet for more than a few weeks.

And what could these hypothetical trials really prove, anyway?