We are now in the era of weight-loss drugs.

Decisions on how these drugs will be used look likely to shape our future health and even what our society might look like.

And, as researchers are finding, they are already toppling the belief that obesity is simply a moral failing of the weak-willed.

Weight-loss drugs are already at the heart of the national debate. This week, the new Labour government suggested they could be a tool to help obese people in England off benefits and back into work.

That announcement - and the reaction to it - has held a mirror up to our own personal opinions around obesity and what should be done to tackle it.

Here are some questions I’d like you to ponder.

Is obesity something that people bring on themselves and they just need to make better life choices? Or is it a societal failing with millions of victims that needs stronger laws to control the types of food we eat?

Are effective weight-loss drugs the sensible choice in an obesity crisis? Are they being used as a convenient excuse to duck the big issue of why so many people are overweight in the first place?

Personal choice v nanny state; realism v idealism – there are few medical conditions that stir up such heated debate.

I can’t resolve all those questions for you - it all depends on your personal views about obesity and the type of country you want to live in. But as you think them over, there are some further things to consider.

Obesity is very visible, unlike conditions such as high blood pressure, and has long come with a stigma of blame and shame. Gluttony is one of Christianity’s seven deadly sins.

Now, let’s look at Semaglutide, which is sold under the brand name Wegovy for weight loss. It mimics a hormone that is released when we eat and tricks the brain into thinking we are full, dialling down our appetite so that we eat less.

What this means is that by changing only one hormone, “suddenly you change your entire relationship with food”, says Prof Giles Yeo, an obesity scientist at the University of Cambridge.

And that has all sorts of implications for the way we think about obesity.

It also means for a lot of overweight people there is a “hormonal deficiency, or at least it doesn’t go up as high”, argues Prof Yeo, which leaves them biologically more hungry and primed to put on weight than someone who is naturally thin.

That was likely an advantage 100 or more years ago when food was less plentiful – driving people to consume calories when they are available, because tomorrow there may be none.

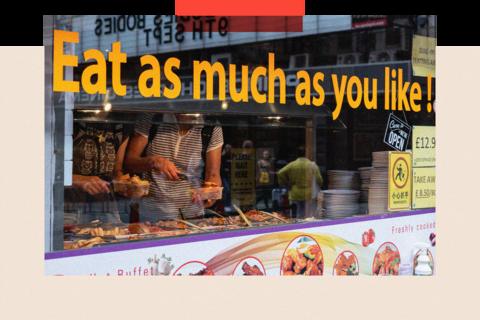

Our genes have not profoundly changed in a century, but the world we live in has made it easier to pile on the pounds with the rise of cheap and calorie-dense foods, ballooning portion sizes and towns and cities that make it easier to drive than walk or cycle.

These changes took off in the second half of the 20th Century, giving rise to what scientists call the “obesogenic environment” - that is, one that encourages people to eat unhealthily and not do enough exercise.