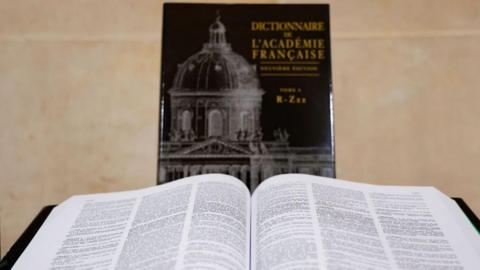

In its press release, the Academy said the dictionary is a “mirror of an epoch running from the 1950s up to today,” and boasts 21,000 new entries compared to the 1935 version.

But many of the “modern” words added in the 1980s or 90s are already out of date. And such is the pace of linguistic change, many words in current use today are too new to make it in.

Thus common words like tiktokeur, vlog, smartphone and émoji – which are all in the latest commercial dictionaries – do not exist in the Académie book. Conversely its “new” words include such go-ahead concepts as soda, sauna, yuppie and supérette (mini-supermarket).

For the latest R-Z section, the writers have included the new thinking on the feminisation of jobs, including female alternatives (which did not exist before) for positions such as ambassadeur and professeur. However print versions of the earlier sections do not have the change, because for many years the Académie fought a rear-guard action against it.

Likewise the third section of the new dictionary – including the letter M – defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman, which in France it no longer is.

“How can anyone pretend that this collection can serve as a reference for anyone?” the collective asks, noting that online dictionaries are both bigger and faster-moving.

Under its president, the writer Amin Maalouf, the dictionary committee meets every Thursday morning and after discussion gives its ruling on definitions that have been drawn up in preliminary form by outside experts.

Among the “immortals” is the English poet and French expert Michael Edwards, who told Le Figaro newspaper how he tried to get the Academy to revive the long-forgotten word improfond (undeep).

“French needs it, because as every English student of French knows, there is no word for ‘shallow’,” he said. Sadly, he failed.

Discussions – lengthy ones -- are already under way for the commencement of edition 10.