I was present at an assisted death in California and witnessed the doctor adding fruit juice to the drug in order to make it more palatable and less bitter for the patient to swallow.

On that occasion the patient, Wayne Hawkins, was unconscious within a few minutes of swallowing the drug and died in around 35 minutes.

Deaths usually occur within an hour although there have been rare cases of it taking several days.

In some other countries that have legalised assisted dying, euthanasia is permitted, whereby a doctor or nurse administers the lethal dose, usually by injection.

Euthanasia is allowed in the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, but even for most supporters of assisted dying here, it is seen as a step too far.

An impact assessment, carried out by civil servants estimated there could be between 1,042 and 4,559 assisted deaths in the 10th year after the law came into force.

That upper estimate would represent around 1% of all deaths in England and Wales.

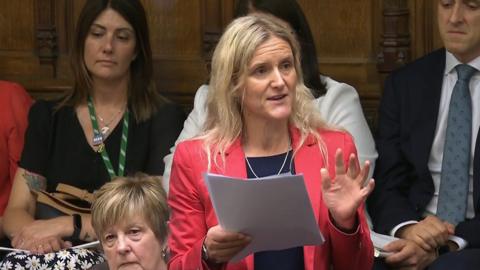

Whatever happens to the Leadbeater bill in the coming months, assisted dying is coming to the British Isles.

The Isle of Man has already approved an assisted dying bill and Jersey is also committed to changing the law.

A bill to legalise assisted dying in Scotland has passed an initial vote at Holyrood, but faces further hurdles. The Scottish bill does not have a life expectancy timescale for eligibility and instead refers to advanced and progressive disease that is expected to cause premature death.

Assisted dying, or assisted suicide as many critics prefer to call it, remains illegal in most of the world.

Modern medicine means that healthcare systems can keep people alive longer than ever before, but often with limited quality of life.

Supporters say that assisted dying gives autonomy and control to patients. For opponents it is a chilling and dangerous step which puts the vulnerable at risk of coercion.

Whatever happens to the bill at Westminster, this heated and polarising debate will continue.